Description

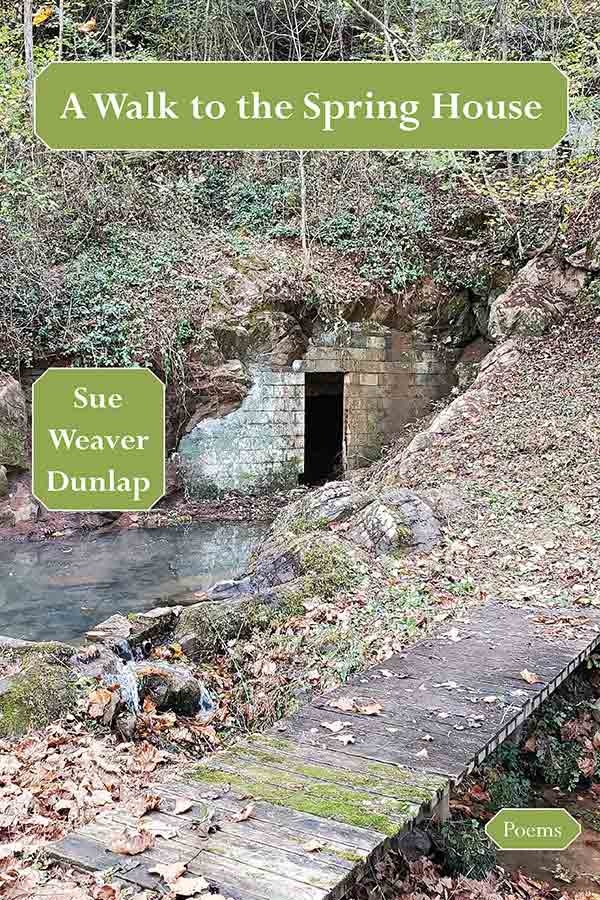

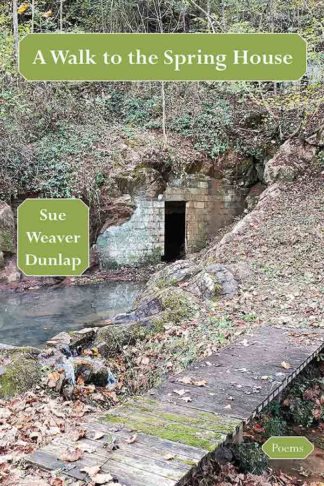

The poems in A Walk to the Spring House capture memories and relics of the poet’s repository of experiences in the Southern Appalachian Mountains. These old mountains and her landscape shape the sections of the book, mountains that ultimately “brace” and “root” the poet who celebrates that she “come[s]” from old. Not only does the poet “pause to praise / the storytellers” and lay claim to her “rooted inheritance,” she also pays homage to her own “call to love.” The poet’s landscape dwells deep in the water, the mines, the mountain farm, the family, the mill town, the hollers, the ancestors—Appalachian humankind and geography—its unique voice and place. These poems stitch together love, hurt, history, beliefs, and landscape, an amazing quilt where “[she] whisper[s] the old sweet of piney roses by the door.”

Praise for A Walk to the Spring House

In this second collection by Sue Weaver Dunlap, each poem “experience to heart to ink” reminds me, despite its small size, of the novels of Lee Smith. Like those longer stories, this gifted poet captures Appalachian humankind as it carries its geography in its genetic code, voice and place are inseparable, and each generation is an embodiment of all that comes before, all the heart, hurt, history, and homage. These poems sing to the beauty of life fully lived against a ragged, raging, and glorious land, and the tender intimacies that run through like arteries and veins. All the while, personal and family history is vividly rendered and respected. The rock, the creek, the body, the work are one beautiful thing always.

—Darnell Arnoult, author of Galaxie Wagon and What Travels With Us

In her luminous new collection, A Walk to the Spring House, Sue Weaver Dunlap not only notes every artifact and totem that has shaped her earth into language, but she also confers benediction, “[pausing] to praise / the storytellers and kneel at [her] own trail crossing.” Indeed, the sacred act of genuflection informs these deeply yearning, prayerful poems, each an altar of remembrance, a reliquary. Dunlap’s speaker is a seer, a medium, who summons and conjures, and traipses miraculously at will through the portal between realms, claiming her “rooted inheritance,” and even raises the dead. These poems imagine a present hauntingly animated by the past, where the souls of ancestry link hands with the living, where ultimately there is no death. These are harrowing, beautiful poems: “the last I love you / at day’s end, morning celebration of one more morning, a call to love.” Sue Weaver Dunlap has fearlessly forged her own book of common prayer.

—Joseph Bathanti, North Carolina Poet Laureate (2012-2014),

and author of The Life of the World to Come

This surefooted account of Appalachian life in transition rings with faith and deep mourning. Sue Weaver Dunlap documents the rituals of making do, getting by, and ultimately, letting go—all in a landscape that is by turns glorious and harsh. She grounds us in plant and place names, native rock deposits, and the tools of farming and cooking. Ultimately, this musical homage to family leaves us wiser: Hearts know no end / when roots of the mighty hardwoods hold fast, / even after wind dies and souls transition.

—Georgann Eubanks, author of The Month of Their Ripening

The rich place names of Appalachia—Tumbling Creek, Ocoee River, Lula’s Holler, Big Frog Mountain, Rip Shin Thicket, Gunstick Laurel—add their own music to the lyrical language in Sue Weaver Dunlap’s new collection, A Walk to the Spring House. The poems sing of remembered visits to the home of “Holler Cousins,” where the voice of adults in an adjoining room is a lullaby for the children snugged together in a sagging bed. Images of gardens, the wild profusion of mountain wildflowers, and “frost glistened tips of grass blades” on an early morning amble balance the pain of cemeteries where babies are buried, the difficulties of life for a father whose picket-line stand has led to blackballing by prospective employers. Readers will long remember taking a walk to the spring house with Sue Weaver Dunlap.

—Connie Jordan Green, author of Darwin’s Breath